Suspension Deep Dive | Toyota 4Runner TRD Off-Road with KDSS

https://ift.tt/37k9lKs

The 2020 Toyota 4Runner represents the 11th year of a fifth-generation design that debuted as a 2010 model. So it’s not new, but that also doesn’t stop it from being more successful than ever. Sales have been on the rise every year since, with a notable spike in 2015 after it got a minor facelift and a freshened dashboard. There were welcome tech updates for 2020.

However, nothing much has changed on the mechanical side in all of that time. Why is that? The answer has two parts. The competition has morphed into crossovers, leaving the 4Runner as one of the last truck-based SUVs standing. It’s also legendary in its own right when it comes to off-road performance and durability. Instagrammers and Overlanders, as well as those who follow Overlanders on Instagram, seem to be magnetically drawn to it.

The one that best encapsulates this vibe is the TRD Off-Road (known as the Trail before 2017), a thoughtfully-equipped model that occupies the second rung in the price ladder. There’s no doubt the TRD Pro is a nice piece, but the TRD-Off Road is far less expensive, much easier to find, and it still has the same locking rear differential, Crawl Control, and the Multi Terrain Select traction control optimization system.

Sure, you won’t get the Pro’s knobbier tires and tricky shocks, but you can replicate both in the aftermarket and still have a good chunk of money left over. And the TRD Off-Road offers a potent option you can’t get on the Pro: KDSS, the Kinematic Dynamic Suspension System. Let’s take a deep dive into the suspension of a 4Runner TRD Off-Road with KDSS.

The 4Runner’s front suspension is very similar to that of the Toyota Tacoma, the dearly departed FJ Cruiser and even the Lexus GX. All of the parts aren’t necessarily interchangeable, but they all use a double wishbone layout with coil-over shocks that is functionally the same.

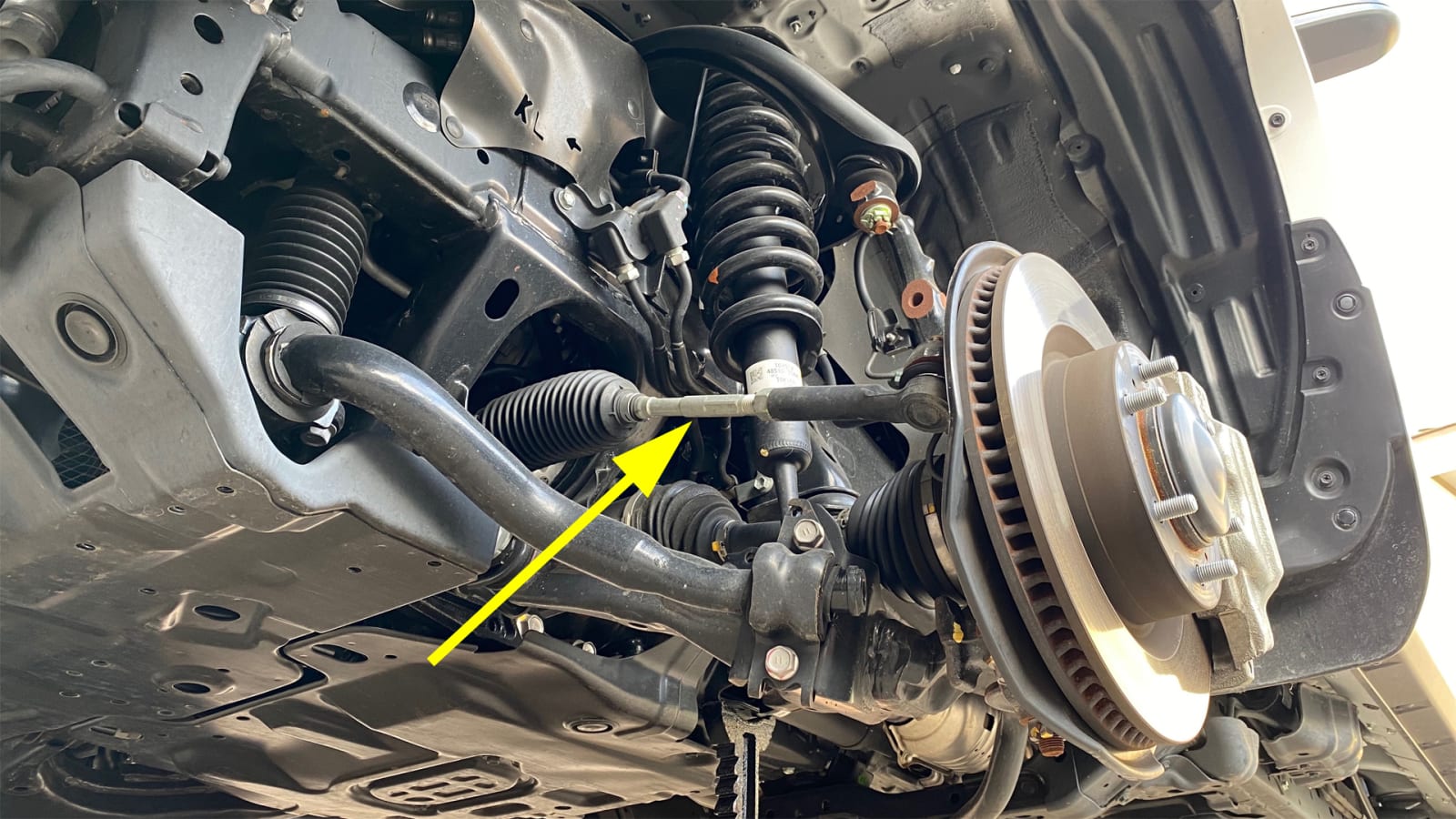

It takes five links to locate a wheel in space, but each use of an A-shaped wishbone counts as two. Front suspensions obviously need to turn, so the fifth link is always the steering linkage (yellow arrow). This one is mounted ahead of the front axle, a position that is generally thought to be superior. It’s also easy to execute when the engine is mounted longways, as it is in trucks and truck-based SUVs like the 4Runner.

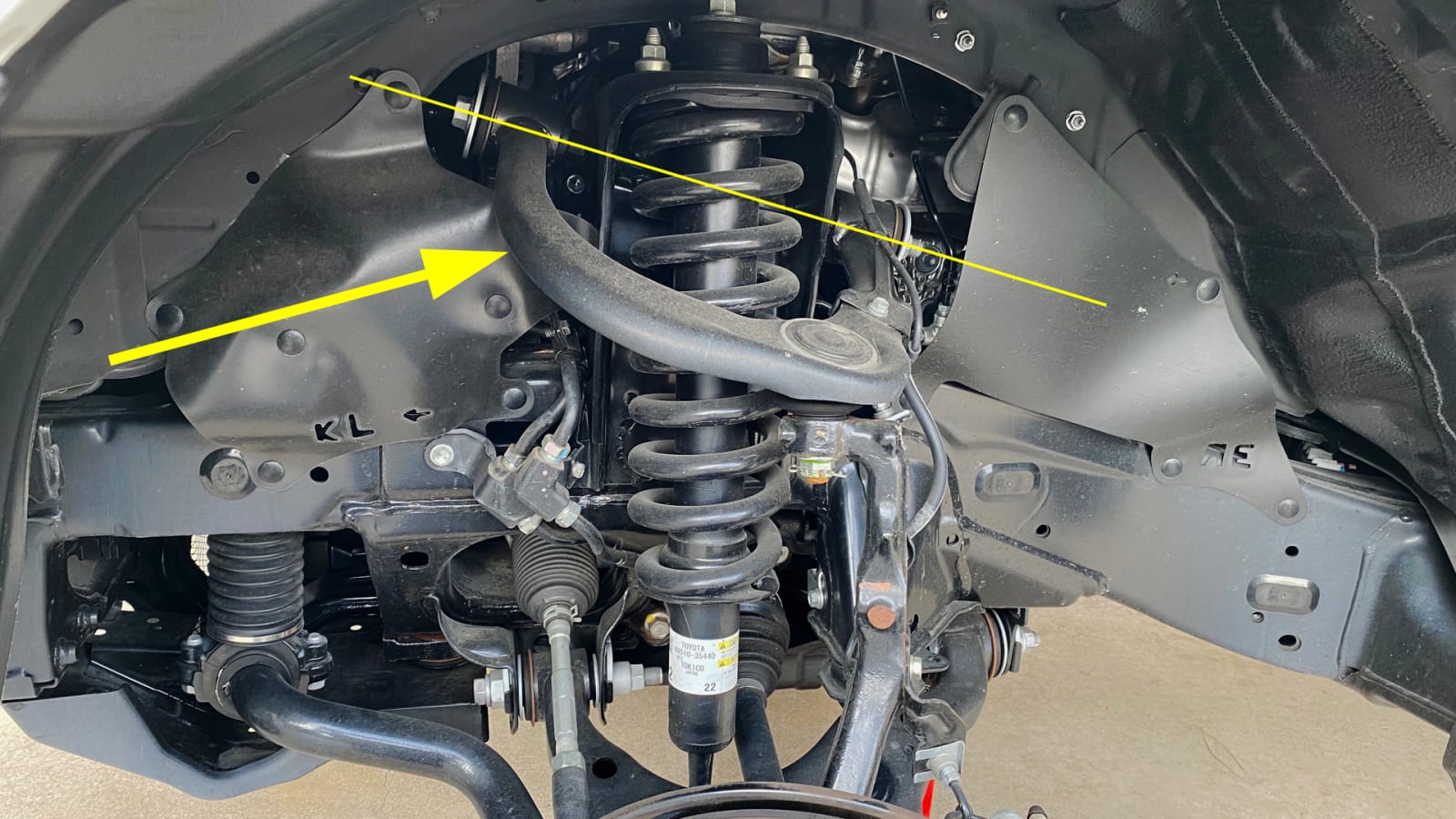

The upper wishbone is mounted high, a position that reduces the load on the arm and its bushings, and makes it easier to optimize steering and camber geometry. Here the pivot axis is angled steeply down toward the rear, an arrangement that produces an anti-dive effect that works against the tendency for nose-dive under braking.

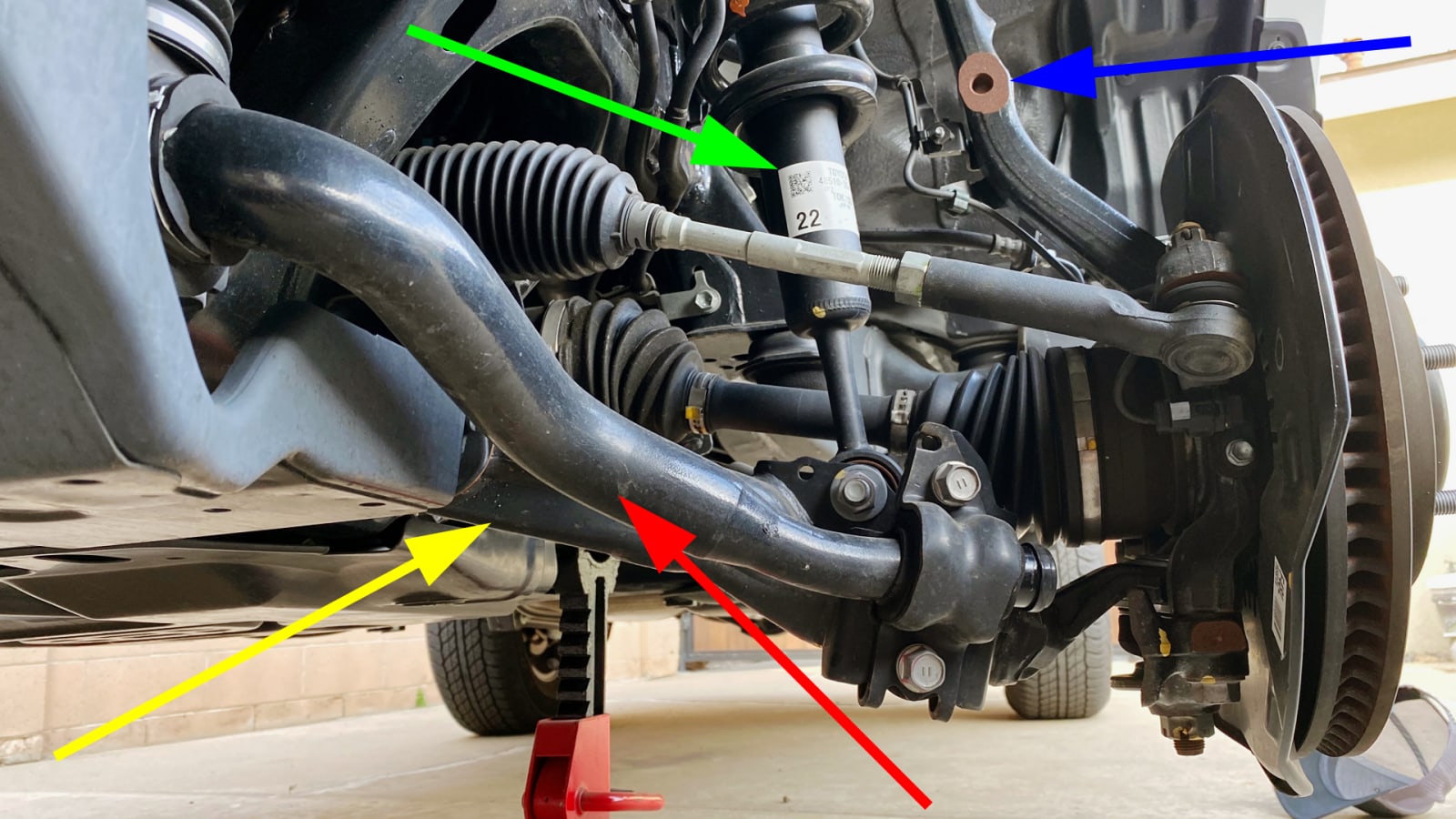

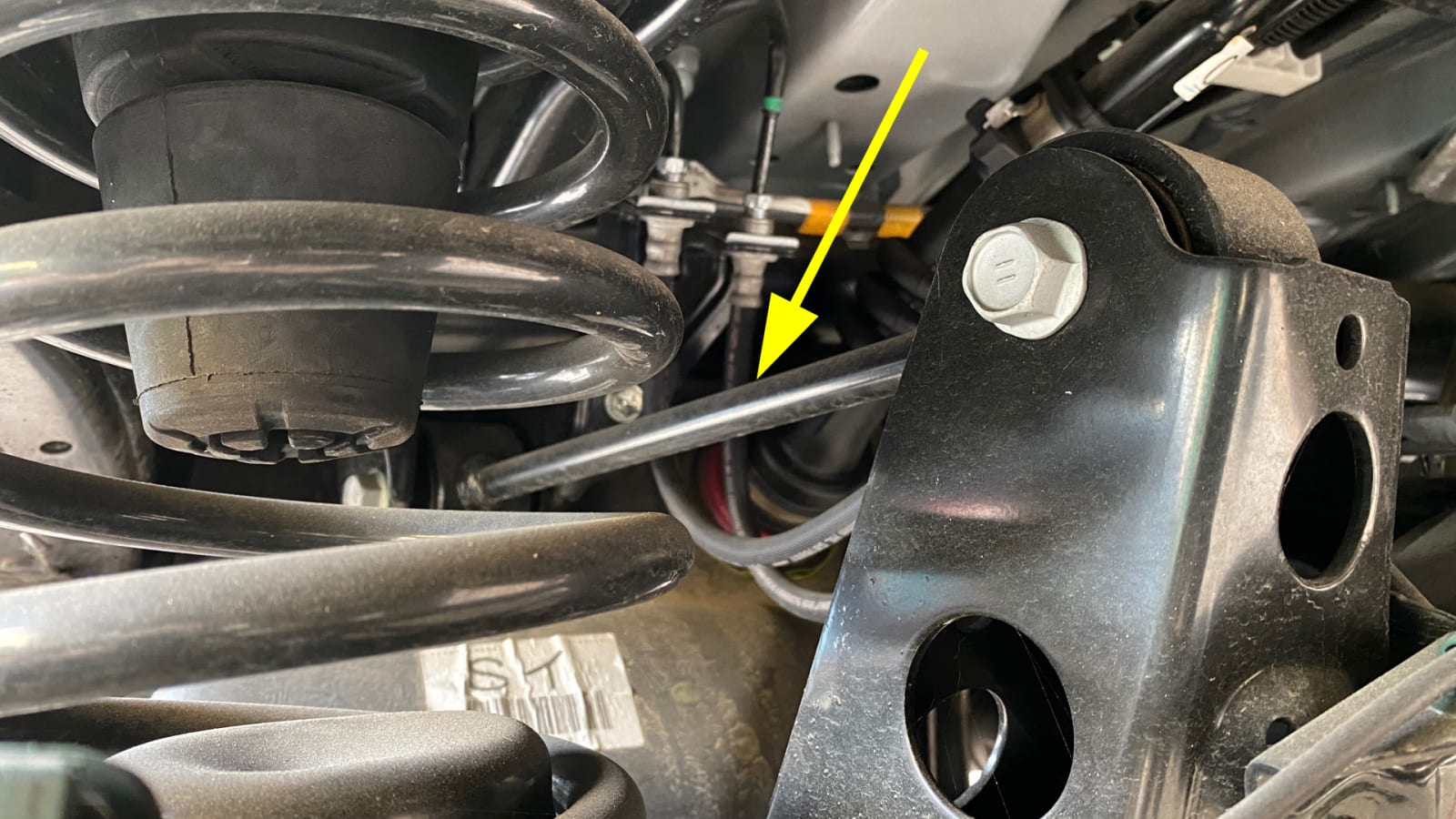

The lower wishbone (yellow) is hard to see here because every system wants a piece of it. The coil-over shock (green) bolts to it after it necks down to sneak past the driveshaft, but the elephant in the room is the massive and weird-looking front stabilizer bar (red) running along the front edge.

Most 4Runners (and all Tacomas) have a smaller front stabilizer bar that loops over the top of the steering to connect with the open hole (blue) in the steering knuckle via a linkage. But this 4Runner has KDSS, which features a larger bar that runs along the front of the lower wishbone and is attached to it directly with an unusual bushing and clamp arrangement.

You want KDSS whether you’re going off-road or not. The system is essentially a pair of fatter stabilizer bars that are better at suppressing body roll (and upset stomachs) on winding roads. But such high roll stiffness is usually terrible off-road, where wheel articulation is king. The magic of KDSS is that it can sense these situations and let the bars go limp and effectively “disappear” at the opportune moment without driver intervention.

The direct bolt-on mounting we see here is central to the way it works.

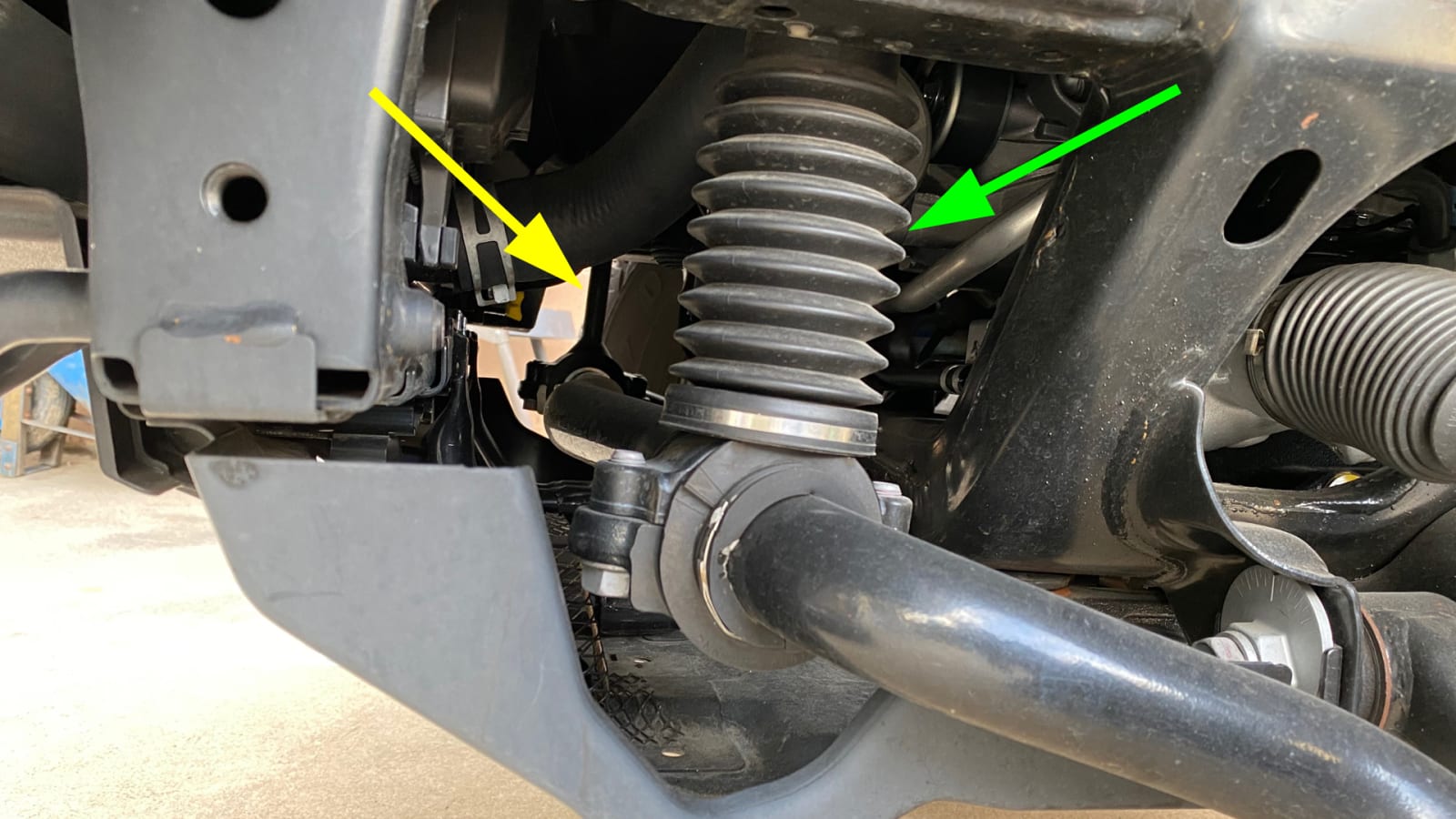

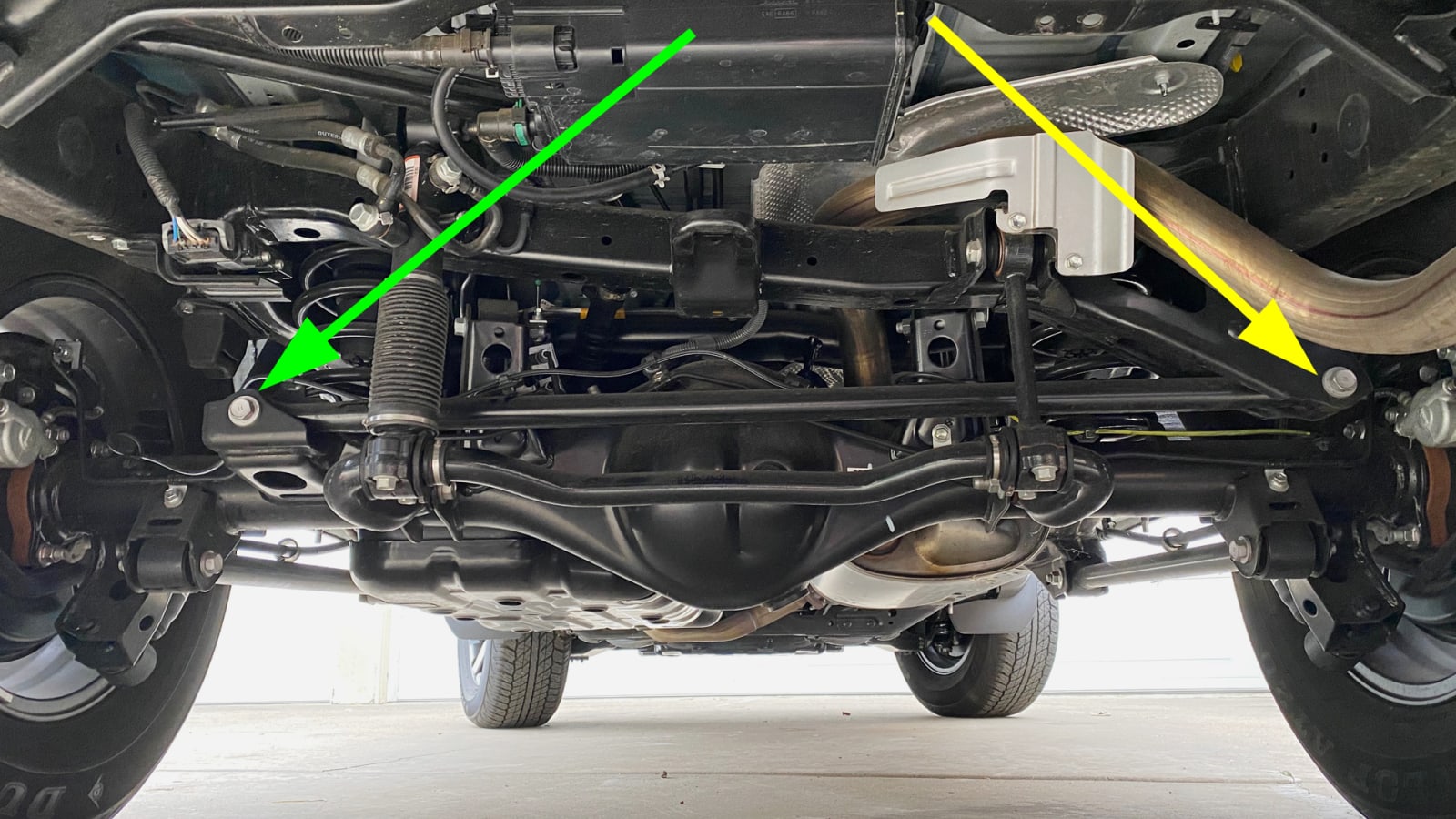

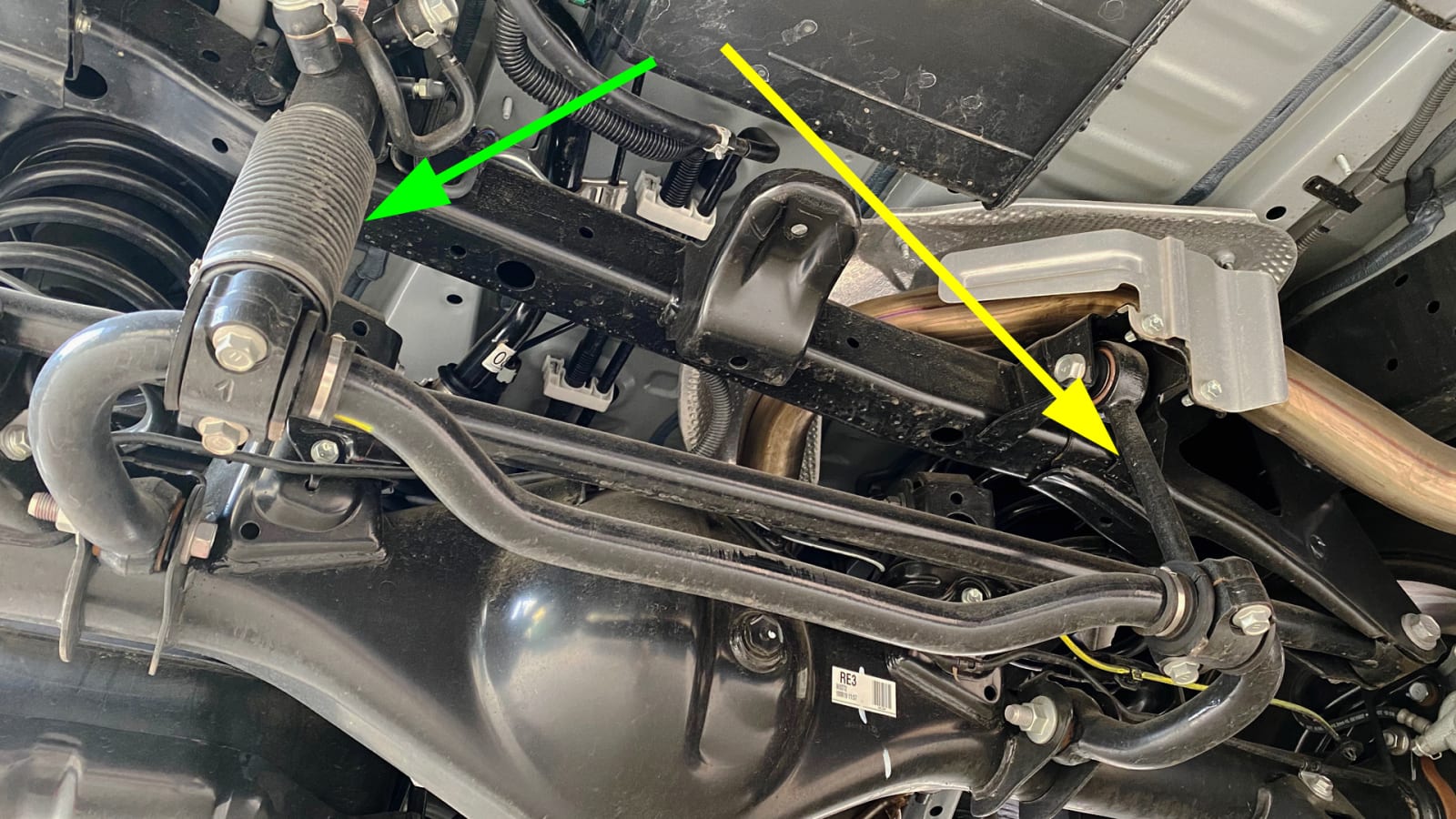

Normally, stabilizer pivot points are fixed rigidly to the frame and the links that connect to the moving suspension elements are out on the free ends. But you can switch that around if you attach the bar ends to the suspension directly. Here the KDSS stabilizer bar’s pivot points are floating on links, with an entirely rigid one on the passenger side (yellow) and a hydraulic cylinder (green) on the driver side.

The hydraulic side stays rigid on paved roads, and that holds the bar’s pivot axis firmly in space so the stabilizer can offer twisting resistance to counteract vehicle roll in corners. Moguls and other lumpy off-road terrain causes the cylinder to go limp, and that allows this corner of the bar to move up and down freely. This action destroys the bar’s ability to generate any roll stiffness, which is a boon to off-road wheel articulation.

The end result is the same as the push-button stabilizer bar disconnect system on the Jeep Wrangler Rubicon, but the method is entirely different and there’s no button to push. But it’s more than that. The ability to disconnect a stabilizer bar means you can mount a fatter one in the first place, and that’s why a KDSS 4Runner corners flatter on winding roads and is better able to handle, say, a rooftop tent than a non-KDSS 4Runner. That same KDSS 4Runner will also articulate better when driven off-road despite its bigger stabilizer bars.

There are downsides. KDSS costs $1,750. It comes with a front skidplate that hangs down a little more to allow for the expanding motion of the front strut. There’s also a limit to how much you can lift a KDSS 4Runner. Estimates vary, but 2 inches seems to be the maximum.

The front bump stop is a rubber chunk that gets squished into the lower wishbone. Those concentric cuts help to make the engagement a bit more progressive, but the specific reason for the pebbly texture escapes me. If I had to guess, I’d say noise reduction.

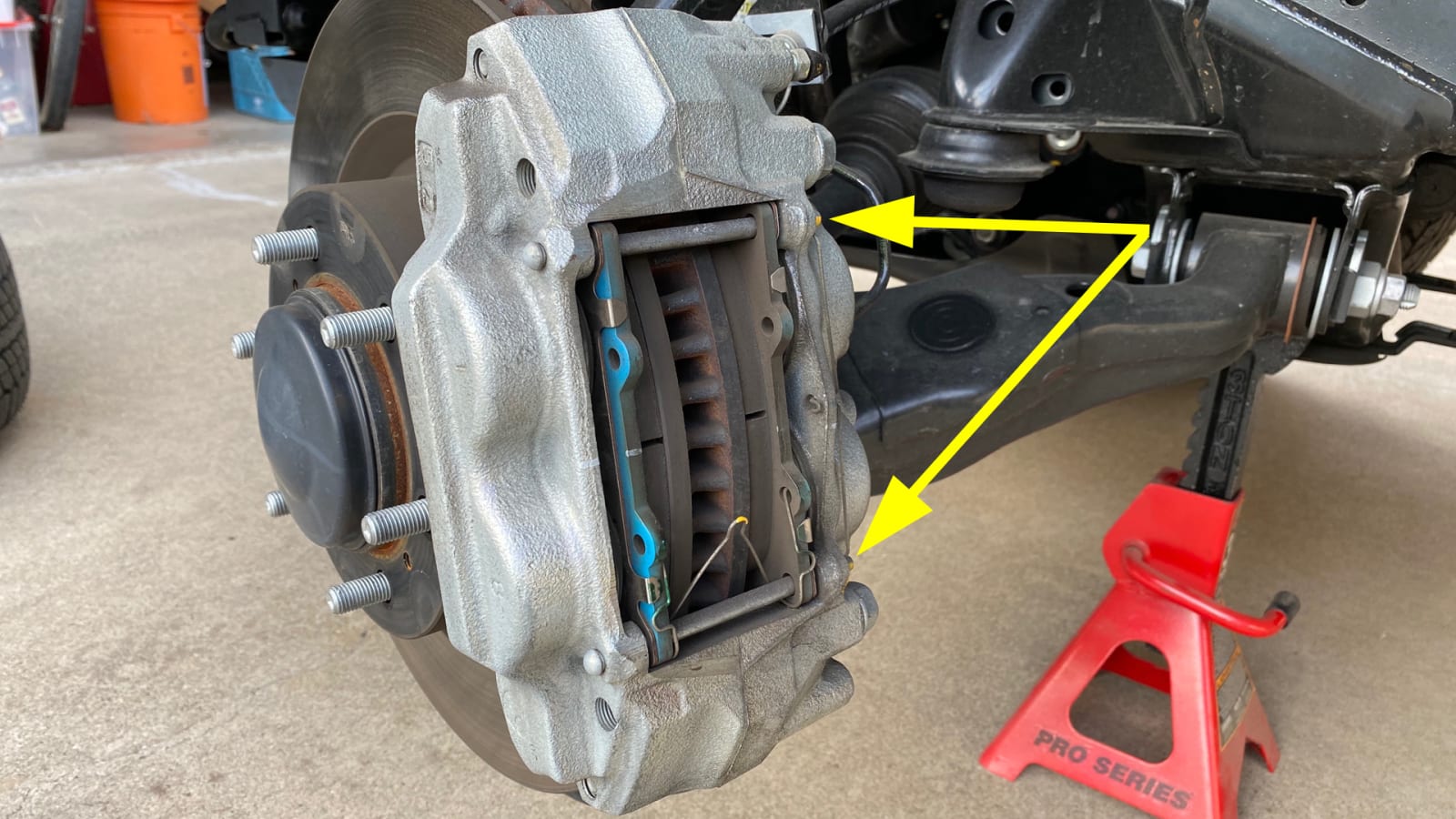

All 4Runners come with sizable front brakes that consist of ventilated front rotors and 4-piston fixed calipers. They employ an open window design, which means a routine brake pad change is a simple matter of removing a pair of pins (yellow) and pulling the pads straight out. As ever, you’ll have to unbolt and remove the caliper if the rotor needs attention.

The rear suspension of the 4Runner uses coil springs and a solid rear axle located by five links. The FJ Cruiser used a similar arrangement, but the Tacoma looks totally different back here because it uses leaf springs.

That prominent bellows indicates another KDSS hydraulic cylinder, but the spare tire is in the way and needs to be cleared out before we can see very much detail.

A five-link axle mounting system should have two links per side, but we can only see one of them (yellow) here. Both would be clearly visible if this were a Ram 1500 or Jeep Gladiator. Instead we see a prominent outboard-mounted shock absorber, a placement that makes them more effective and allows them to nestle up to the tires where they’re less likely to be snagged by trailside rocks. They’re also ridiculously easy to access if you want to swap them out.

Each side’s elusive “missing link” can be found inboard of the coil spring and just above the axle housing. We’re now up to four.

There are bump stops, and then there are bump stops. The blocky one (yellow) is the actual bump stop. Its cupped shape hugs the axle itself without need for a flat landing pad, and the small void is there to soften the initial blow.

There’s also a structure within the coil spring itself, but this is more of a rubber secondary spring (green) than a bump stop. This gives the rear suspension a dual-rate function that comes into play when the vehicle is loaded. Toyota engineers shy away from progressive coil springs because of durability and noise concerns, so they chose this route instead.

Link number five is easy to see with the spare tire absent. It’s a lateral panhard rod that keeps the axle from moving left and right. The fixed end (yellow) is attached to the frame and the moving end (green) is connected to the axle. Longer is better here, because a big swing radius reduces the amount of left-right translation that will occur as the link moves through its arc. For the same reason, it’s even more critical for it to start out level at rest. The slight rise apparent here will almost certainly disappear with a couple of people on board.

The KDSS rear stabilizer is hard to miss with the spare tire out of the way. As in the front, the bar ends are fixed to the suspension and the pivot points seem to float. The passenger side pivot link (yellow) is always rigid and the driver side link is a hydraulic strut (green) that can either be rigid or limp depending on whether the vehicle is cornering on asphalt or riding the moguls off-road.

The fact that it’s back here at all is unique because most stabilizer bar disconnect systems only work at the front. KDSS, on the other hand, actually needs to be present at both ends for it to work at all.

When cornering, the front and rear KDSS struts are “in phase” and both experience either compression or tension at the same time. The pressure is balanced, and so the pistons within the struts don’t move. Moguls put the system in “opposite phase” in which one end is in compression while the other experiences tension. This large pressure differential allows the struts to move freely. The bars wobble about like a table with a short leg, but they can’t generate any roll resistance.

The rear brakes are of two minds. The primary stopping power comes from a solid disc and a single-piston sliding caliper. But the rotor also has a deep “hat” section (yellow) that indicates the presence of a drum parking brake.

The TRD Off-Road rolls on 17×7.5-inch aluminum alloy wheels and P265/70R16 tires. That translates to 31.5 inches tall in old money, but the combination isn’t light. Lift with your knees.

The 4Runner stands apart in a world that is increasingly dominated by crossovers. The suspension we just examined is a big part of its appeal, not only in concept but also in Toyota’s dedication to the design details that make it a legitimate performer off-road.

But the 4Runner will soon have company. The Ford Bronco will return this year, and all indications point to a layout that is similar to the venerable 4Runner. Will it stack up well against the Toyota? The answer is only a few months away.

Contributing writer Dan Edmunds is a veteran automotive engineer and journalist. He worked as a vehicle development engineer for Toyota and Hyundai with an emphasis on chassis tuning, and was the director of vehicle testing at Edmunds.com (no relation) for 14 years.

Auto Blog

via Autoblog https://ift.tt/1afPJWx

January 23, 2020 at 11:54AM