Audi Repair Shop Doylestown

Call 267 279 9477 to schedule a appointment

GREAT FALLS, Montana — This is not the last time I’ll write this: No stock vehicle on sale in the U.S. today can match the capabilities of the

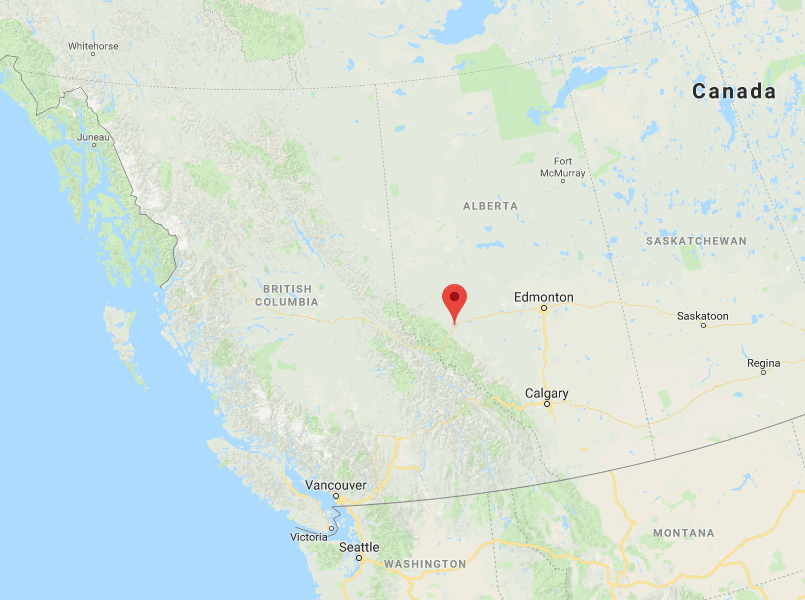

Rubicon. I discovered that during the first here-goes-nothing off-road excursion on my Rubicon Alaska Cannonball run, two days of crashing around Cadomin in Alberta,

. This adventure is also where I discovered muskeg, a bog muck I prefer to call “swamp guts.” That’s a picture, above, of our first meeting. Getting high-centered was my fault, not the

. You’d get hung up on things, too, if you were carrying 800 pounds in your rear. But we’ll get to that.

We left off in Tuktoytaktuk. I departed the Arctic on a Sunday afternoon with my patched spare tire, headed for a meet-up with the MudBudz Wheelin’ crew in Hinton, Alberta. Turning back from boreal climes, the whole ball of Earth welcomes all who return. Sparkling lakes and mossy tundra framed Yellow Brick Roads made of dirt. This time I’d drive slow enough to avoid another unfortunate meeting with volcanic shard, if possible. E-load-rated BFGs, the equivalent of a 10-ply tire, were stock fitment on the JK Wrangler. On the JL,

switched to a C load rating, the equivalent of a six-ply tire. The thinner construction means lower rolling resistance, a softer sidewall for a better ride, and better gas mileage.

For 2.5 hours, I bounded and rebounded over 90 miles of pulverized highway to Inuvik. I filled the tank, then hit the Dempster at the onset of another drawn-out Arctic twilight. A hazy moon hung above the spruce as I descended to the MacKenzie River ferry crossing. As on the drive up, a million times I wanted to stop for photos, but I had to get across the Peel River further down the road before the ferry stopped. I never got to see the southern stretch of the Dempster in daylight. On the run north, I’d arrived at the Peel at dawn. I did get to see the Northern Lights again, the fifth straight night of “

Star Trek”

interludes. The lights were so bright I could shoot them with my phone.

I also saw two bright yellowish dots glowing down the road, reflecting the wave of illumination thrown by the Mopar five-inchers. Eyes. Around 50 yards away, I made out a massive moose. I crept closer. Moose are crazy. I’d have taken a flat tire over a bad date with a 1,300-pound ungulate. The moose began running from shoulder to shoulder across the road. After a quarter-mile, he hopped into the brush along the roadside and disappeared.

Gone

. I don’t understand why, but remote Alaskan and Canadian roads are frequently lined by ditches seven feet deep. Hidden moose pop out of them the same as hares and housecats do in the Lower 48. I think this is nuts.

In the wee hours, at the end of the Dempster, I filled the tank and jerry cans and headed southeast down the Klondike Highway. I slept in a pullout through another charcoal night, waking up to forests aflame in fall colors. The natural beauty on the Klondike Highway in autumn could stand in for one of the wonders of the world, and I had it to myself except for occasional traveler headed the opposite way. Again, I ask: How is this a secret?

A strange totem on the side of an abandoned house greeted me at the end of the Klondike, a mystical agent stamping the end of a mythic Arctic. I turned left toward Whitehorse.

I camped in Teslin for a few bipolar days — 45 degrees in the sun, 7 degrees overnight. When I pulled up camp on a Thursday, I stood atop the hill across Teslin Lake for a final gaze. The streak of watery blue felt like a barrier, and I was back on my side of it. On the other side, I’d been on campaign, in strange lands with strange tribes that I’d struggle to make the home crowd believe.

I had an appointment at a

in Grande Prairie, Alberta — 844 desolate miles away — the following day for a new windshield and two new tires. I had a full tank, one full jerry can, and plenty of time. At my first stop 162 miles later, I didn’t get gas — my first mistake. The Alaskan Highway gets sleepy around 9:30 pm, and goes to bed by 10.

After the sun went down, I drove by

after gas station, all of them closed. I figured the next station would be open, because one of them

had

to be open, right? No. At Toad River, Liard River, Mucho Lake, the next station was never open. I reached a place called The Lodge at 10:15 p.m. They’d shut down their pumps 15 minutes earlier. I declined a room, emptied my gas can and kept on. My second mistake.

By the time I pulled up next to the pumps at the Tetsa River Lodge at 2 a.m, I’d been driving with the low-fuel light on for more than 10 miles. The Internet says the 169-mile stretch of Highway 6 from Ely to Tonopah in Nevada is the longest stretch of road in the Lower 48 states without a gas station. I’d driven a 410-mile stretch of Alaskan Highway that had gas stations, not one of them open. My American mind couldn’t comprehend it.

The next station I could be sure was open was in Fort Nelson, 70 miles away, so I slept in the small gravel lot next to the lodge pumps. Actually, I first took a long chew on the evening’s bitter lesson, realizing I’d have to haul like

Rider to cover the 434 miles to Grande Prairie in time, and I’d be way late for the MudBudz meet-up. Then I slept.

In the morning, as soon the lodge opened at 7 a.m, I pulled up to the pump. A woman walked out and said, “We have no gas. We’re bone dry. I don’t know what to tell you.” She stood there, looking at me. The lodge’s giant sign next to the highway that read, “WE HAVE GAS AND DIESEL,” had lied to me. I stared at the scenery. As usual, it was beautiful. A wonderful place to screw up. The woman told me I could either call for “a

very

expensive tow,” or nurse the Jeep to the pullout at the crest of Steamboat, 11 miles away. There’d be hunters passing who’d have gas cans and might sell me some.

Now I’d find out how well I could

a Wrangler.

I crept to Steamboat unmolested, this being an early Friday morning well past the end-of-season. I waited 20 minutes. No passer-by had gas cans. I realized I could be there for hours waiting for just the right hunter with just the right mindset to stop and sell his gas to a rube in exchange for American dollars. I got a text from MudBudz asking how I was doing. Fort Nelson was 50 miles away, I told MudBudz I’d walk, figuring my luck would be better on the move. I could sort out a ride back in town. MudBudz advised against the hike. Bears.

I didn’t think I had a choice. I started the walk, turning back after going downhill for half a mile. I saw two road crew workers in the pullout, explained my situation, and asked if the road continued downhill to Fort Nelson. They said yes, adding, “Our shift is done in 10 hours. If we see you’re still out here, we’ll take you ourselves.”

I cranked up the Rubicon, turned on the hazards, and babied the Jeep to a Husky gas station in Fort Nelson. Four-door Wranglers get a larger 21.5-gallon tank. I put in 21.12 gallons. Then I filled both gas cans. Canada wasn’t going to fool me again.

I blasted off for Grande Prairie, pulling into the dealer not far off closing time. The service rep was kind enough to get me a windshield, but the tires were on backorder everywhere. Thankfully, Kevin in Tuktoyaktuk had done such a good job patching that I wasn’t worried about it. Then I left for a late-evening MudBudz rendezvous and met three of the crew: Kevin, the trail guide with his Jeep Hatchet; Spencer, who would save me from killing myself and the Jeep the following day; and Chelsea, owner of a Jeep called Punkin, and MudBudz’s voice of reason.

I followed Kevin to the campsite, trying to keep up in blinding snow, on a snaking two-lane road from Hinton to Cadomin like a special stage in the Rally of Finland. This was the first time in 16,000 miles of the Rubicon Alaska Cannonball that I thought, “I don’t know if I’m going to make it out of this drive alive.” Why didn’t I flash my lights to get him to slow down? Because I figured if this is how Canucks do it, let’s give it a shot. The Jeep’s windshield wipers contributed to the excitement, being perhaps the most disappointing wipers I’ve used in the 21st century. The driver-side blade gathers ice where it meets the arm, lifting the blade off the glass, leaving a wide streak of slushy water refreshed with every swipe. I sat up over the blind spot, hunched down under it, or leaned over into the passenger’s seat. Later, I’d ask Jeep folks about it, and they’d say, “I’m surprised Jeep didn’t fix that,” since it was also an issue on the JK, or, “It’s a Jeep thing,” like this is the price you pay to be in the club.

In camp I met the rest of the crew: Christine, the face of MudBudz on

; her boyfriend Dwayne, the owner of Turd; and Trevor, Chelsea’s boyfriend and Punkin’s other parent. The snow fell along with the temperature, but the Canadians know how to build a bonfire. There were a few drinks, many laughs, much heat. The next morning, I loaded up on the home-cooked breakfast, then met the convoy. Kevin’s rig Hatchet is a 2016 Rubicon with a 3.5-inch lift on 37s. Punkin is a 2013 Sahara with a two-inch lift on 35s. Turd was Frankenstein’s monster, a 1990 YJ with a carbureted 1973

350, a 700R4 transmission, a Currie front diff,

LS8.8 rear diff, and 37s. A stout gang.

Crystal Falls was our first stop. The area around Cadomin, a mining area, is narrow, rocky two-track through evergreens. The long, gentle slopes are connected by short, steep, rock-and-rut-filled runs, and washouts that lean a rig

way

over. Magnificent landscape to look at, but hazards hide everywhere under the snow. Pools form in depressions, creating troughs of water that obscure the rocks. Then the tops of the pools freeze, then snow covers the ice. Because the MudBudz folks regularly haunt the area, they know where the dangers are. I did not. Christine had had the foresight to ask Spencer not to bring his Jeep so that he could ride shotgun and guide me.

I didn’t think that was necessary. I was

completely

wrong.

On the trail, I’d break the ice and wade through a pool, and Spencer would say, “Watch out for that rock.” I didn’t see a rock. WHAM. Oh.

That

rock. It happened once more — the warning before the WHAM — then I started to figure out what rocks looked like. Other times, I couldn’t see the rocks, like when we stopped at the bottom of a short, acute incline covered in snow. Spencer pointed out the line and listed the traps. All I could do was follow directions. I never saw the stumps and divots that had us bucking while I gunned it, Spencer telling me to “Give ‘er” whenever I’d let off the throttle too soon. If Spencer hadn’t been with me that day, I’d still be in Cadomin ordering replacement parts, assuming I made it off the trail.

On the way to the next sight, Ruby Falls, I got stuck for the first time — high-centered coming out of a bit of muck that didn’t seem that deep. If I’d stayed on the throttle I might have made it over. I tried a combo of lockers, reversing, and throttle, and Spence and Dwayne tried rocking the Jeep. No joy. Kevin hooked a strap to Hatchet and pulled me out. The 800 pounds of gear I’d accumulated behind the front seats explained the sag in the hindquarters. A dumpy rear end isn’t the ideal stance for tackling the wet Alberta wilds. And muskeg, I would learn, loves any lumbering thing it can swallow.

Spencer pointed out three lines through the muskeg, I tried the middle one, the result being the photo at the beginning of this story. If the Jeep hadn’t been weighted like a half-ton pickup, and if I’d known what I was doing, I might have made it through. Hatchet strapped up and pulled me out again.

I succeeded with a few other serious obstacles, however. We crossed an absurd mud pit that I’d seen on YouTube, one you couldn’t drive straight through. You dropped in, worked your way from pit to pit navigating small islands of dirt and trees and avoiding hefty logs, then climbed out. A lot of throttle, a lot of flying filth, a lot of “Shut up and hold on.” I drove well enough not to sink us. The Jeep gets the real credit.

We headed back to camp after a full day, stopping to check out the wild horses and ceremonial teepees on some First Nations land. I joined in harvesting firewood for the evening’s inferno, working up an appetite for a fantastic meal of steaks, potatoes, beans, and a buffet of sides. The next morning, we decided on a run to MacKenzie Falls. My front left tire had a slow leak earned during the first day’s running when I slid the corner into a grunchy bit of mud and rocks. I told Kevin, Dwayne, and Spencer I needed to fix the flat. Dwayne grabbed his floor jack and impact wrench and went to work with Kevin and Spencer. By the time I’d reorganized my Trasheroo, ratchet straps, and gas cans, Kevin was bolting the flat to the spare carrier. If teamwork makes the dream work, I’d just watched the game from the bench. Dwayne said, “That’s the difference between Jeepers and Jeep owners.”

It had warmed up overnight, melting most of the snow. That meant slick trails and more mud. Christine rode with me, again pointing out lines and repeatedly issuing three-word throttle advice: “Stay in it!” Or, as Spence had said the day before, “Give ‘er!” Leaned way over a through a washout, I again chose a bad line. The Jeep slid to the right, slamming into the mud berm. The impact crunched the front right fender, pulling the latter third of it off the body, put a couple of small dents in the door, and left a few lasting scratches as I drove off. I’d been wary of the fender LEDs, figuring I’d one day tear them off or break the light. I’d come about as close as I wanted to making that happen, yet the fender stayed attached, and the LED light didn’t break.

Then came a ridiculous series of mud pits snaking through more trees. It took a couple of minutes, a few resets in reverse, and a lot of throttle, but I got through it. The Jeep got a bath a couple of miles down the trail when we crossed a pool that put water above the 33-inch tires. No sweat. But my Pentastar V6 steamed more, and for longer, than every other engine in the group.

We made MacKenzie Falls, threw snowballs, took photos, and turned back. Dwayne told me that some of the trails we’d run were part of the Nuxalk Grease Trail (formerly Alexander MacKenzie Heritage Trail), and we’d done the easy bits. It’s a blessing I never found the trailhead. I’d have been bear food.

We struck camp and said goodbyes. MudBudz were the perfect guides who led me through the perfect test for the new Wrangler. On top of that, they stuffed me with delicious food, and taught me about everything from harvesting firewood to the Canadian obsession with macaroni and cheese. One day they’ll start charging to host wandering Yanks, and they should.

I pointed the Jeep south, to America and the end of The Great North. The sky turned to dusk as I wove through the whitecapped peaks of Jasper National Park. I spent my last pitch-black Canadian night crossing the Promenades des Glaciers into Banff National Park, past Lake Louise, and onto Calgary, where I spent the night. I filled up at Shell in the morning and examined the Jeep. Absolute filth. And the best stock adventure rig you can buy for the money.

I crossed the border at Coutts, making U.S. landfall in Montana. It felt like a foreign country. Having set up shop in Great Falls, I’ll hit the

for a couple of new tires, then ride the

Divide Trail to Mexico, stopping for more wheeling along the way. But first, a long,

long

, shower.

Related Video:

from Autoblog https://ift.tt/2LecTDJ